Troy Norred was on his way home for Thanksgiving in 1998 when he had his flash of genius. It was the middle of the night, his wife was driving the family car, and his four children were asleep in the back. He'd just finished his shift at the hospital, where his workweek often exceeded a hundred hours. Two days shy of thirty-one, Norred was a fellow in the cardiology program at the University of Missouri. For more than a year he'd been stewing over an idea, and so powerful was his sudden insight now—surface area in the aortic root!—that he told his wife to pull over. He made a sketch on a napkin. That sketch would become the breakthrough that led to U.S. Patent No. 6,482,228, "Percutaneous Aortic Valve Replacement," granted in November 2002 by the United States Patent and Trademark Office. It would also become the basis for an idea that Norred would spend the next four years failing to interest anyone in financing the development of—not his superiors in the cardiology department at Missouri, not the venture- capital firm that flew him to Boston to hear his pitch, not the cutting-edge innovation guru at Stanford who initially encouraged him but then ended the conversation, not the product-development people he signed non-disclosure agreements with at Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, Johnson & Johnson, Guidant, and others. The idea was for a collapsible prosthetic aortic valve that could be fished up through an artery with a catheter and implanted in the hearts of patients who suffered from failing aortic valves.

By September 2003, Norred had all but given up on his dream when he and a colleague were strolling the exhibition hall at an important cardiology congress held annually in Washington, D.C. They came upon a booth occupied by a California startup called CoreValve. With increasing alarm, Norred studied the materials at the booth. He turned to his colleague: "That's my valve!"

According to documents filed in a legal case that lasted more than three years and wound its way through multiple federal courts, Norred tried unsuccessfully to discuss a licensing deal with CoreValve. He says he reached out to the startup's then-chief executive, a Belgian Congo–born medical-devices entrepreneur and investor named Robrecht Michiels, who told him that a license would need to wait until after CoreValve had grown out of the startup phase. (Michiels denies saying any such thing.) Norred tried to follow up with CoreValve, but his calls and letters went unanswered. Years passed. Norred settled into private practice and then, in 2009, he saw the news online: CoreValve had sold itself to Medtronic for $775 million in cash and future payments. Today, collapsible prosthetic valves fished up through an artery with a catheter and implanted in the aorta are well on their way to becoming the standard method of replacing worn-out heart valves. The annual market has already surpassed $1.5 billion and is expected to grow in the coming years by orders of magnitude.

When Norred first saw CoreValve's version of his patented invention, he did not know that the U.S. patent system had entered an era of drastic change. Starting in the early 2000s, the rights and protections conferred by a U.S. patent have eroded to the point that they are weaker today than at any time since the Great Depression. A series of Supreme Court decisions and then the most important patent-reform legislation in sixty years, signed into law in 2011, have made it so. The stated purpose of the reform has been to exterminate so-called patent trolls—those entities that own patents (sometimes many thousands of them) and engage in no business other than suing companies for patent infringement. The reforms have had their desired effect. It has become harder for trolls to sue. But they've made it harder for people with legitimate cases, people like Norred, to sue, too.

According to many inventors, entrepreneurs, legal scholars, judges, and former and current USPTO officials, the altered patent system harms the independent, entrepreneurial, garage-and-basement inventors, who loom as large in our national mythology as the pilgrim and the pioneer. In the words of Greg Raleigh, a Stanford-educated engineer who came up with some of the key standards that make 4G networks possible, "It has become questionable whether a small company or startup can protect an invention, especially if the invention turns out to be important." Some call it collateral damage. Others maintain it was the express purpose of the large corporations to harm inventors. But, in the end, the result is the same. The Davids have been handicapped in favor of the Goliaths. Those who believe that innovation's richest sources lie as much in garages as in corporate R&D labs have grown fearful. "We clearly had the world's best patent system, based on the results," says Palo Alto venture capitalist Gary Lauder. "And that is going away."

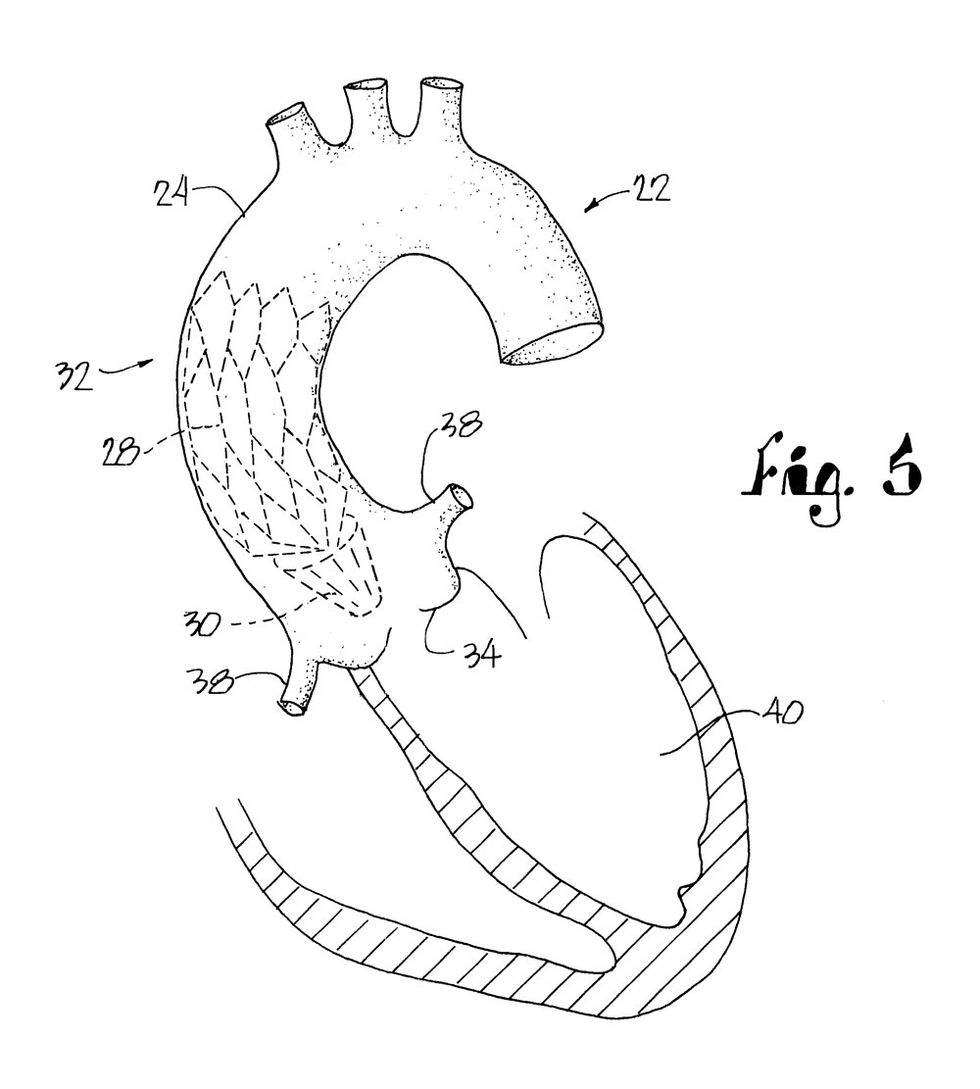

As a resident at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in the mid-1990s, Troy Norred saw an elderly male patient who was in all ways healthy except for a failing valve in his aorta. At the time the only way to treat that condition was to open up the man's chest, stop his heart, bypass it, carve out the old valve and suture in a rigid artificial one. The patient was too old for such a procedure. He died. "Why can't we replace his valve in a way that would not create such havoc on his system?" Norred asked himself. "What would such a replacement look like?" Most important, he realized, the valve would need to withstand the tremendous pressure of blood pumping constantly through it.

On that Thanksgiving drive, he thought he had figured it out. His idea involved the surface area of the tubular aortic root and an expandable nitinol stent, also tubular, with a pig valve attached to it. The stent would expand against the tissue wall of the ascending aorta, anchoring the new valve in place and creating a seal without the need for barbs or staples or sutures, which tend to break over time. The surface area was the key. The more area the stent could expand against, the stronger it would adhere and the better it would keep the valve in place.

The insight invigorated him. He went to a local slaughterhouse and had the packers chainsaw-cut the hearts out of pig carcasses. He dropped the hearts—famously similar to human ones—into vats of liquid nitrogen. He stored them at home in the fridge, exasperating his wife. He talked his way into a cold lab at the university's agricultural engineering department and made epoxy models of pig hearts and pig aortas and pig aortic valves. He built proto type artificial valves and inserted them into the models. With the help of a materials engineer, he mathematically modeled his invention. The key to the math turned out to be a load-bearing equation.

All that work, however, was for naught. For his fellowship research project, he proposed a set of experiments that would further test his invention. The estimated cost was high: $70,000. The proposal was rejected, and would continue to be, in other venues and by other entities, until Norred eventually gave up.

The term "patent troll" was invented at Intel in 1999. This was the heyday of the PC- computing era, and Intel's office of general counsel was constantly receiving threats from people who wanted to sue for patent infringement. Some were established competitors angling for cross-licensing deals. Some appeared to be failed startups trying to wring something from their last remaining assets: their patents. Others were lone-wolf inventors no one had ever heard of. And still others were groups of lawyers who'd accumulated patent "portfolios" and were now seeking a return on their investments.

None of these plaintiffs were looking to create and sell products based on the inventions described in the patents. They were "nonpracticing entities," or NPEs, and their main goal was to use the menace of a lawsuit to pry a licensing fee from the company.

Intel's legal department wanted to come up with a term that would suitably vilify these new irritants. Citing the "Three Billy Goats Gruff" folktale and its avaricious goblin crouched underneath the bridge, an underling on the Intel legal team had an idea. Patent troll. Everyone loved it. "Make no mistake," says Ron Epstein, a lawyer in Intel's patent and licensing department at the time, "it was a pejorative term consciously created to make people feel bad about asserting their own patents."

The plan worked beyond anyone's imagining. Perhaps no figure is more reviled in Silicon Valley today than the patent troll. Often that disdain seems to cross into a loathing for patents themselves. According to Terry Rae, a former deputy director of the USPTO, "There's an anti-patent feel" in Silicon Valley. "It's almost religious." The attitude is perhaps most typified by Elon Musk, who has declared the ideas contained inside Tesla's patents free to anyone for the taking. Echoing Henry Ford, who openly pined for the abolition of the patent system, Musk has described patents as "intellectual property land mines" that inhibit progress.

That attitude has spread, like technology itself, from the West Coast to the rest of the country. A largely collaborative project evolved among Silicon Valley's giants to lobby Washington. They formed Beltway pressure groups with names like the Coalition for Patent Fairness. Their message was clear: Something must be done to combat the scourge of the troll. Those pressure groups funded studies, including one conducted by legal scholars at Boston University in 2011 that proclaimed lawsuits by trolls to be "associated with half a trillion dollars of lost wealth to defendants from 1990 through 2010, mostly from technology companies"—assertions that have been undermined by subsequent studies. Even so, a report from the President's Council of Economic Advisors in 2013 repeated those same claims.

But according to Epstein and other Silicon Valley insiders, the real goal of these lobbying efforts wasn't to kill trolls or even to curtail patent litigation. Though big tech corporations still spend many billions a year on R&D, the outlay has shifted from the R to the D—that is, the developmental work of bringing to market that which has already been invented. This means that big companies increasingly obtain their innovations not from their own efforts, but by acquiring them from startups, small inventors, and universities.

One way to make those acquisitions cheaper is by weakening patent protection. You make it harder to sue. If a patent no longer protects an invention as strongly as it once did, a big tech company is in a much better position to negotiate a lower price for licensing a patented invention.

After CoreValve was sold to Medtronic in 2009, Norred's attorney, James Kernell, sent a letter to the company, seeking a license. Norred and Kernell were optimistic. After all, in April 2010, Medtronic had lost in spectacular fashion an infringement lawsuit brought by its archrival, Edwards Lifesciences. Edwards had asserted a patent for a catheter- implanted replacement aortic valve that was much less similar to Core Valve's device than was Norred's. (Medtronic would eventually pay Edwards close to $1 billion.) A yearlong back and forth between Norred and Medtronic ensued. Early on things looked promising, especially when, Kernell says, he verbally floated a figure of $40 million that a Medtronic attorney indicated was in the ballpark. "I thought we pretty much had a deal in place," Kernell says. Norred was ecstatic. But then communication began to slow, and in December it stopped entirely. Calls and emails went unreturned. Medtronic had gone dark.

Just a few weeks later, in January 2011, a new bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate. This was the America Invents Act, the jauntily named patent-reform law that was the culmination of years of lobbying by many large companies led by those in the technology sector. On its way to the White House, the bill received more bipartisan support than any piece of legislation yet voted on during the Obama administration. It was designed to undermine the business model of the patent troll, and it contained a potent new mechanism for voiding nettlesome patents. But it also had an unintended consequence: The new bill drastically handicapped inventors in favor of big companies. Inventors like Norred.

Medtronic, it turns out, was one of the bill's many corporate proponents.

Norred wasn't a troll, and the decision to sue did not come easily for him. His lawyer told him that the cost to litigate could exceed half a million dollars. Norred did not have half a million dollars. He considered letting it drop and moving on with his life, but in the end he couldn't. "It's hard to give up on something you've worked so hard on," he said. His attorney agreed to work on a contingency basis. On February 6, 2013, Norred asserted his patent.

Whenever an independent inventor sues for infringement today, an immediate suspicion attaches to the case. The anti-patent feeling is such that to assert one is to become stigmatized as a troll or, worse, a con artist or a quack. But there's another way to look at these litigants. It could be that an inventor- plaintiff is a modern-day Bob Kearns, the Michigan engineer who spent decades fighting the global automobile manufacturing industry over the intermittent windshield wiper. They made a movie about it called Flash of Genius.

Though individual inventors such as Norred are the plaintiffs in less than 10 percent of the total number of patent infringement suits filed in the U.S., they are, like Kearns, tenacious—even more so than conventional patent trolls, or even the huge companies that sue and countersue and make headlines (Apple v. Samsung v. Apple). That 10 percent figure comes from a study led by a legal scholar at the University of Illinois named Jay Kesan. It would appear that most inventors who sue believe they're in the right to such a degree that they're willing to battle until the bitter end, Kesan says. There's an obvious reason why. "They have so much of their personal selves bound up in their inventions."

Norred Currently lives with his wife and teenage son—three other children are away at college—in rural Ada, Oklahoma, where he's had his cardiology practice since 2002. Aside from his McMansion of a house, Norred's twenty-acre property contains a complex of outbuildings: a garage, a chicken coop, a barn, and a workshop, where he spends most of his time when not seeing patients.

To get to the workshop you walk past a swimming pool and, nearby on the patio, a large wood-burning oven that resembles a stone igloo. (Norred designed the oven. He once tried to heat the pool with it.) An exercise room with mirrors on the walls occupies one of the outbuildings. Equations scrawled in grease pen cover the mirrors as Norred works out a problem involving "anaerobic thresholds" and "capillary density" related to another of his inventions—an exercise contraption that would combine an elliptical with a lateral pull-down machine. His wide-open workshop has smooth, gray, poured-concrete floors. There are drill presses, a miter saw, a lathe, a table saw, a MIG welder, a massive workbench. Various brands of nitinol stent are laid out on the workbench; Norred has been systematically subjecting them to stress tests. A cabinet contains drawers full of cardio medical devices that he brought in here and deconstructed. A bench press sits in the middle of the shop. ("I've got an idea for a new type of bench press," he says.) An enormously heavy lead vat turns out to be a nuclear processing station, with which Norred once made his own nuclear isotopes. Somewhere in storage he has an entire cath lab that he acquired from a clinic in Georgia. He wanted to use it to conduct tests on his valve. A cardiologist friend of Norred's said, "He has a tendency to get to talking about something and you look at him and think: You're out of your mind."

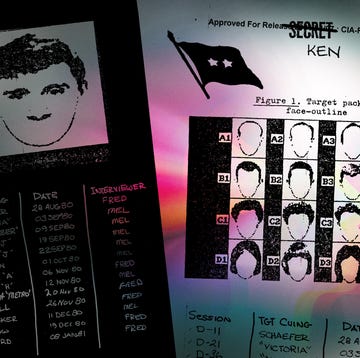

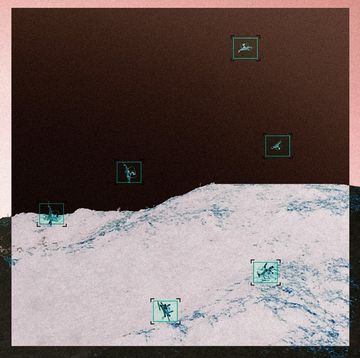

In October 2013, eight months after filing his lawsuit against Medtronic, Norred got word of a troubling development. His patent had been IPR'd. The letters stand for inter partes review, which refers to a sort of extrajudicial system that exists inside the USPTO. Any party can petition a special tribunal within the Patent Office to challenge the validity of any already granted patent. The petitioner effectively says: This patent is junk, and here's why, forcing the patent's owner to defend it in a trial before a panel of three administrative judges—people with both technical and patent-law backgrounds, often former patent examiners. For a patented invention, an IPR is an existential test. To lose is to vanish from the system as an invention. Most of the time the entity making the IPR challenge is a company that's been sued for patent infringement. The motivation is obvious: Get the patent invalidated and the lawsuit disintegrates. So that's what Medtronic tried to do.

IPRs were established with the America Invents Act in 2011. A large portion of the AIA addresses the issue of so-called patent quality. During the '90s and early 2000s, amid the blossoming of so much groundbreaking technology, it is widely understood that the USPTO granted a raft of patents it shouldn't have. Historically, this is not uncommon. Whenever explosions of technology have occurred in the past, the Patent Office has struggled to keep up with the resulting surge in applications. The fuel trolls feed on is the vague, too broad, illegitimately issued patent. A company couldn't launch a new product, it seemed, without potentially infringing scores of other patents. IPR tribunals were seen as a way to clear the system.

But they also have had an unfortunate side effect. IPR tribunals make it easier for sophisticated defendants to kill patents held by legitimate inventors. The first IPR challenges started rolling in to the USPTO in September 2012, and the first decisions were handed down a little more than a year after that. By July 2014, in the middle of Norred's IPR ordeal, the tribunals were invalidating 70 percent of the claims in the patents that went to trial. Randall Rader, at the time the chief judge of the Federal Circuit—which is, among other things, the nation's appeals court for infringement suits—has called the tribunals "patent death squads." Not surprisingly, large corporations have a different view. As Medtronic's chief patent counsel said publicly at a Washington event last year, "We love the IPR system."

The term "trial" in the IPR context is more figurative than literal. Both sides present evidence and the testimony of witnesses. But all of it is done through deposition and digitally filed documents, with the exception of a single physical hearing at which both sides' attorneys give oral arguments. Still, it can get expensive. The IPR alone ended up costing Norred more than $100,000.

On October 8, 2014, Norred was deposed at one of his lawyers' offices in Kansas City. From the get-go, the encounter was tense. It became clear that a major pillar in the company's argument would be that Norred's valve was an amalgamation of already invented technology and hence not a patentable idea. In a very real sense Norred was now required, for a second time, to prove that his invention was a real invention.

Title 35 of the United States Code contains a sequence of conceptual tests an idea must pass before it can be deemed patentable. The idea must not be a naturally occurring thing or a scientific principle. The idea must be "novel." And the idea must not be "obvious" "to a person having ordinary skill in the art." That is, your idea—if, say, it's for a prosthetic heart valve— cannot be an amalgam of bits and pieces of already invented technology, what's called "prior art," whose combination would be obvious to an authority in prosthetic heart-valve design.

Back in 2000, when Norred first submitted his patent application, he didn't realize that someone had already patented an idea for an aortic valve that could be implanted without surgery. Dr. Henning Rud Andersen, a Danish cardiologist, has said that the idea for a "transcutaneous" valve first came to him in 1989. The lead patent examiner working Norred's case indicated that Andersen's patent represented major "prior art" that Norred and his patent attorney had to contend with in order to have the patent approved. At first Norred freaked. He'd been scooped. But as he read through the Andersen patent, he grew calmer. His valve was different in a fundamental way. Andersen's valve is anchored to the aortic wall by a kind of "brute force," Norred says, like a suspension rod. "Whereas I rely upon dispersing that force over a larger surface area. The reason that's important biologically—you're talking about tissue that's not rigid, and the more force you put on it, the more likely you are to tear it." The USPTO agreed. Patent granted. (Dr. Andersen eventually licensed his patent to Edwards Lifesciences, which then used it to sue Medtronic-CoreValve for patent infringement, extracting that $1 billion payout.)

Now Norred was being forced to go through the process all over again. Only this time Medtronic was hurling prior art at him that he either had never seen before or had considered irrelevant. Taking those inventions together, Medtronic argued, Norred's valve was obvious.

In many ways, there was nothing new about Medtronic's tactics. Arguing that a patent is invalid is the oldest and most fundamental of patent-infringement defenses. When sued, big companies unleash swarms of high-paid lawyers, who hire still other people tasked with searching the planet for any lethal prior art that might assassinate a patent. There are those who specialize in this. It is an actual profession: prior-art searcher.

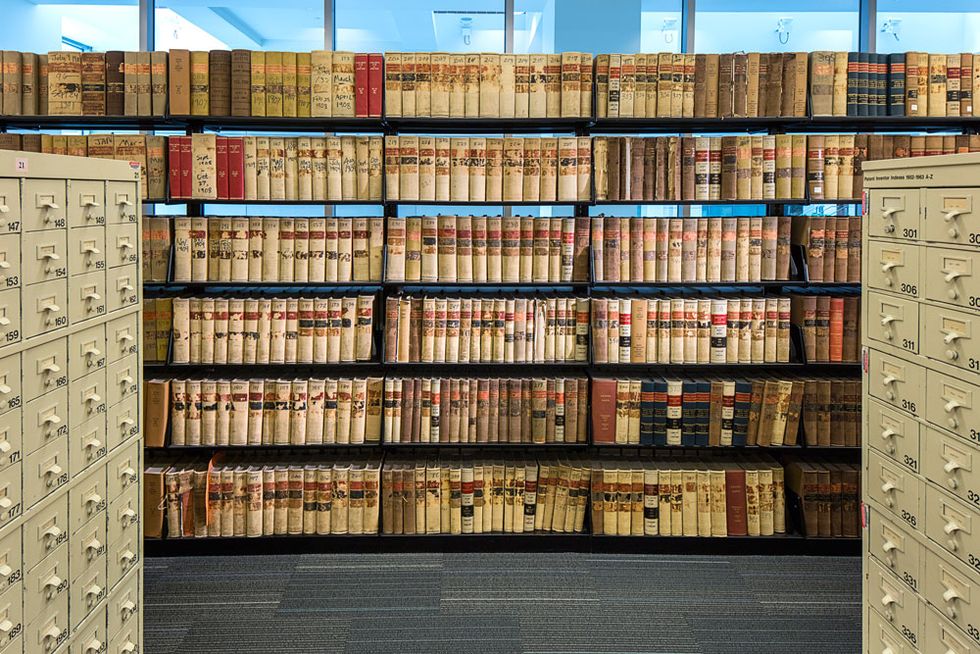

Off the lobby of the main USPTO building in Alexandria, Virginia, is the Public Search Facility. If the country's patent archive could be said to have a home, this is it. On its way to accepting its ten millionth patent, the digital archive is immense and getting only bigger—a kind of Borgesian library of civilization's creep. Finding prior art is therefore both difficult and easy. There is so much to sift through yet so much to choose from. Late in the afternoon on almost any weekday, sitting at the cubicles and staring at the computer screens in the search facility's large main room, the prior-art searchers are there. They can charge more than $100 an hour.

The oral hearing for Medtronic v. Norred took place on an afternoon in late January 2015. Inventors themselves almost never attend oral hearings, and neither did Norred. It's just lawyers and their documents and their words. Typically each side gets about an hour to present its case, including rebuttals. Judges often telecommute to these things, so the lawyers at the podium end up addressing their arguments to flat-screen TVs outfitted with videoconferencing systems that sometimes go on the fritz.

To an outsider, an IPR hearing can seem almost totally incomprehensible. You understand the individual words coming out of the lawyers' mouths, but any larger unit of meaning fails to find cognitive purchase on your mind. Partly that's because of the highly technical nature of the inventions, and partly it's because of the nature of patent law itself. A patent is made up of a set of claims, and the claims are chunks of prose that are meant to describe the parts of an invention. When the claims of a patent overlap with those of a prior one, the claims are said to "read" on the prior art. And so an IPR hearing becomes a painstaking interpretive exercise in linguistic analysis, with one set of lawyers trying to pick a patent's language apart, and the other desperately trying to defend the words as they stand in the original. "The IPR isn't an effort to figure out whether an inventor invented something," says Ron Epstein, the former Intel attorney. "It has turned into a process where you use every i-dot and t-cross in the law to try to blow up patents." He adds, "There isn't a patent that doesn't have some potential area of ambiguity. If you set up the office so that no ambiguity is allowed, no patents will survive."

At the oral hearing, Norred's attorneys argued that the prior art cited by Medtronic was irrelevant. One of those pieces of art, a valve patented by an inventor named DiMatteo, wasn't designed for use in aortas. Though the words "aortic valve" do appear in the DiMatteo patent, the invention, which has not been developed into a commercial device, is actually designed to replace the venous valve. And the other prior art describes surgically implanted valves, not ones that would go in with a catheter, as Norred designed his valve to do.

Three months later, in April 2015, the tribunal ruled: "Petitioner has shown, by a preponderance of the evidence," that DiMatteo was lethal to three of the twenty-four claims in Norred's patent. Unfortunately for Norred, those three claims were the core of the invention. Without them, his patent collapsed into meaninglessness and Medtronic was immune to his challenge. Norred's attorneys immediately appealed the tribunal's decision. In May 2016, the appeals court ruled against him. It was over.

Back in Ada, Norred was of course dejected. It was as if he had been wiped clean from history. It was as though he had never invented anything at all. The notion galled him. Around the time of the IPR decision, Norred was working extra hours at a hospital outside Pittsburgh in order to pay for his legal costs. One of the other cardiologists there mentioned to Norred that he wanted to train in transcutaneous aortic valve replacement. Norred couldn't resist mentioning his invention. The doctor gave him a look of disbelief. "I've never heard of you," he said.

*This article origionally appeared in the July/August 2016 issue of Popular Mechanics.