How Did Work-Life Balance in the U.S. Get So Awful?

Among all advanced nations, we rank 28th -- barely better than Mexico. Why's our work-life balance so bad if leisure is growing? Because single moms are growing faster.

The United States is the greatest country in the history of everything, if you just listen to its leaders, and a disgrace among developed countries, if you just read international surveys. Our health care system is famously expensive and inaccessible. Our education system is famously broken. Oh, and our income inequality? It's just famous.

The OECD Better Life Index, released last week, feeds the American instinct toward both jingoism and self-deprecation. In housing access and family wealth, it concludes that the U.S. really is the best country in the world. But we rank 28th among advanced nations in the category of "work-life balance," ninth from the bottom.

This raises a thorny question: If we're so rich, why are we working so hard that we don't even have time to cherish the fruits of our productivity?

There are some simple reasons why the U.S. places far below Scandinavia and other European countries among work-life metrics. We work longer hours to make all that money. So we have less down time. Also, we don't have national laws, like mandatory paternal leave, that alleviate the burden on working moms.

The surprising fact is that American leisure time has actually been increasing for most families for decades, and American men work less today, and have more down time, than ever recorded. Even if you consider that to be bad news (and many do), less work should improve just about any definition of work-life balance. Still, the most important reason why we rank barely above Mexico is the increase in single mothers who, in the U.S., face an extraordinary burden relative to their overseas counterparts.

Surprise: Leisure Time Is Growing (But Not For All)

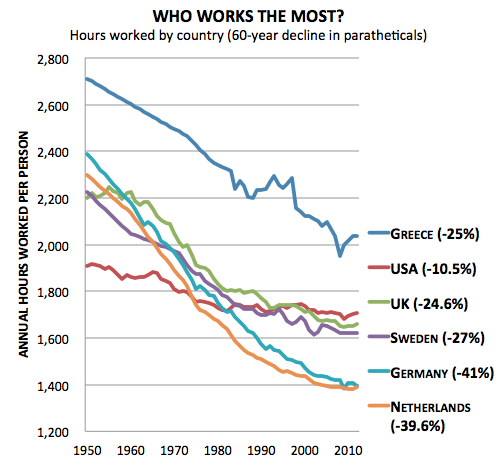

Since 1950, personal hours worked have fallen dramatically all over the developed world, thanks to advances in overall productivity and the shift away from certain kinds of time-intensive manufacturing. They've fallen the most in European countries and the least in the U.S.

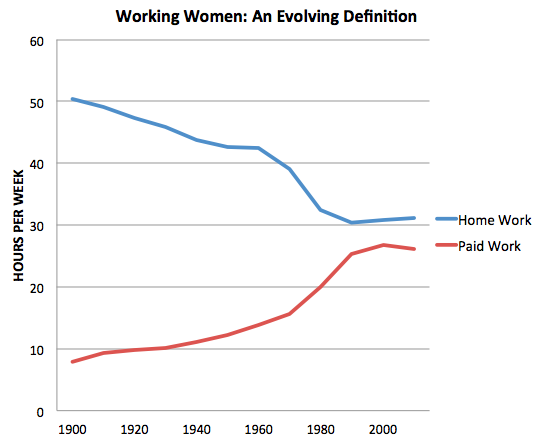

But those gross averages hide the fact that the workweek has undergone two parallel revolutions in the U.S: More paid work for women and less paid work for men. Hours worked by moms have doubled since 1960. Higher education attainment and the rise of the service sector has allowed many women to trade chores for paychecks, as this graph shows (data via Valerie Ramey).

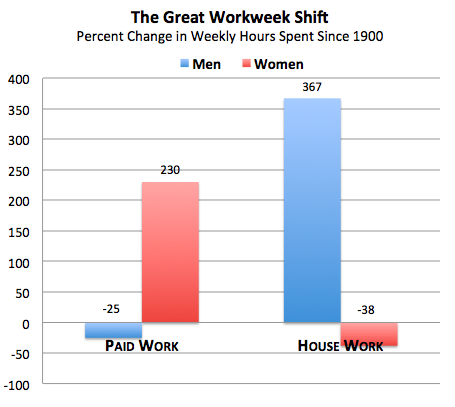

In the meantime, men have picked up some of the slack at home. In the 20th century, the typical working woman's week hours rose by 230 percent; in parallel, men are doing about 370 percent more housework.

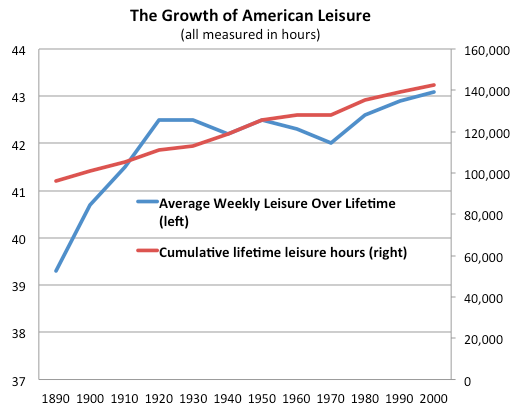

"Leisure" means different things to different people. But to economists it means time spend not working -- either the kind that involves doing chores or the kind that involves doing Excel. In the last century, lifelong leisure time in the U.S. has grown significantly, due to at least three factors: (1) the decline of the workweek, which most affected men; (2) technology making house work more efficient, which most affected women; and (3) people living longer in retirement, which affected both men and women.

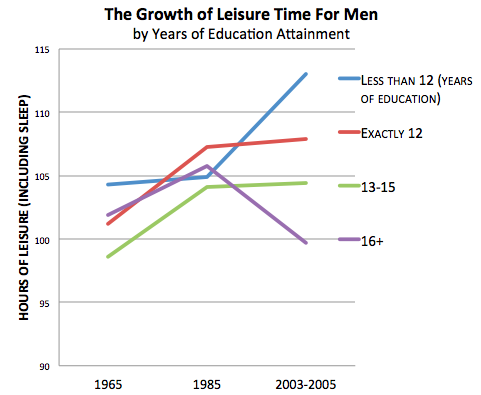

You might think the increase in leisure would be highest among the rich, since nations have generally earned more leisure time as they've become more productive. But strangely, it is the least educated and poorest men who have seen the highest gains in leisure. This has created what economist Eric Hurst, among others, calls, "leisure inequality," which mirrors income inequality. Poor working men have more leisure time than ever, but the highest educated men have less downtime than they've had in 50 years.

The OECD's "work-life" balance measure counts long hours, leisure time, commuting time, satisfaction with job, and the employment rate of mothers with school-age children. Although the U.S. places near the bottom overall, it actually places among the top countries in commuting time and job satisfaction. And as you can see, we're making strides in overall leisure time as well. But the most important category where we fall far behind other rich countries is with mother -- especially single mothers.

The Single Mom Crisis

Women are the primary breadwinners in 40 percent of U.S. households today. But in most of those families, women are the primary earner because they are the only earner. One if four houses are now led by a single mom, who earn an average income of just $23,000.

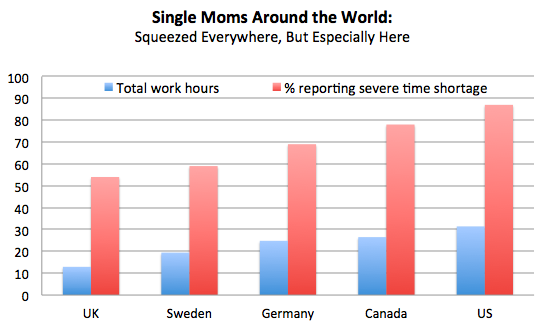

Balancing work and leisure without a partner isn't easy no matter where you live, but single working mothers feel a particular pinch in the U.S., for two reasons. First, the U.S. has the fourth-highest share of single mothers in the OED. Second, they work the longest hours and have more children than most rich countries, according to a study of family time. "Lone mothers in the US have less available time than lone mothers in any of the other countries" the researchers studied.

Single mothers are more likely to work than the average adult -- after all, the vast majority of them simply must -- but they're also more likely to work less. In the U.S., where single mothers work the most, only 4 percent punch in more than 50 hours a week.

So when you hear that American work-life balance ranks poorly, remember that there really isn't any such thing as "American work-life balance." Instead there are intersecting trends -- only a handful of which I've touched on here -- showing that, although the workweek has fallen, the changing composition of families has put tremendous time-stresses on more mothers. Overall, research shows that lower-income men have never had more downtime, while working single mothers have never been more common. The first part is a problem. The second is a crisis.