One Tuesday morning this fall, I strapped on a Kevlar vest and slid into the passenger seat of a gray Ford Interceptor sedan, the souped-up Taurus that replaced the Crown Vic as America’s default police car a decade ago.* (And has since been replaced itself: Ford no longer produces police cars, only SUVs and pickups.) This model has several features that are not available for civilian use, including a siren on the roof and a V6 Mustang engine under the hood.

That came in handy when Kevin Roberts, a talkative, thoughtful third-year cop, steered us onto Connecticut’s Interstate 84 for the day shift. We were heading toward Waterbury, whose interlocking expressways are his to patrol. Roberts was in the left lane going 80, and I had the uncanny experience of surveying the highway from his point of view. How many times have I been on the other side—overtaking some slowpoke, 12 over the limit, only to see a rack of siren lights in the rearview mirror and ask myself: How slowly can I complete this pass?

Roberts and I were waiting for that moment of panicked recognition. He knows people resent that the police are always speeding, but he says it’s the only way to do the job. You can’t drive the speed limit or below, because no one wants to pass a cop. The highway’s self-organizing system would disintegrate and traffic would slow to molasses. “Everyone’s at 10 and 2,” he said as we made our way past another stone-faced commuter. It’s the morning rush, and drivers are on their best behavior. “You’ve got to wait for people to spread their wings.”

Roberts is not out to ticket every last speeder, because that would be impossible. “We know not everyone is going to go 55, 65, we’re realistic,” he said. “Not everyone is going to go the speed limit.” When he’s not responding to an accident or a crime, he sees his role as corrective. Sometimes that means loop after loop on the city’s highway landmarks, the Mountain (a steep slope to the east) and the Mixmaster (a decked highway near the city), without stopping to set a trap at all.

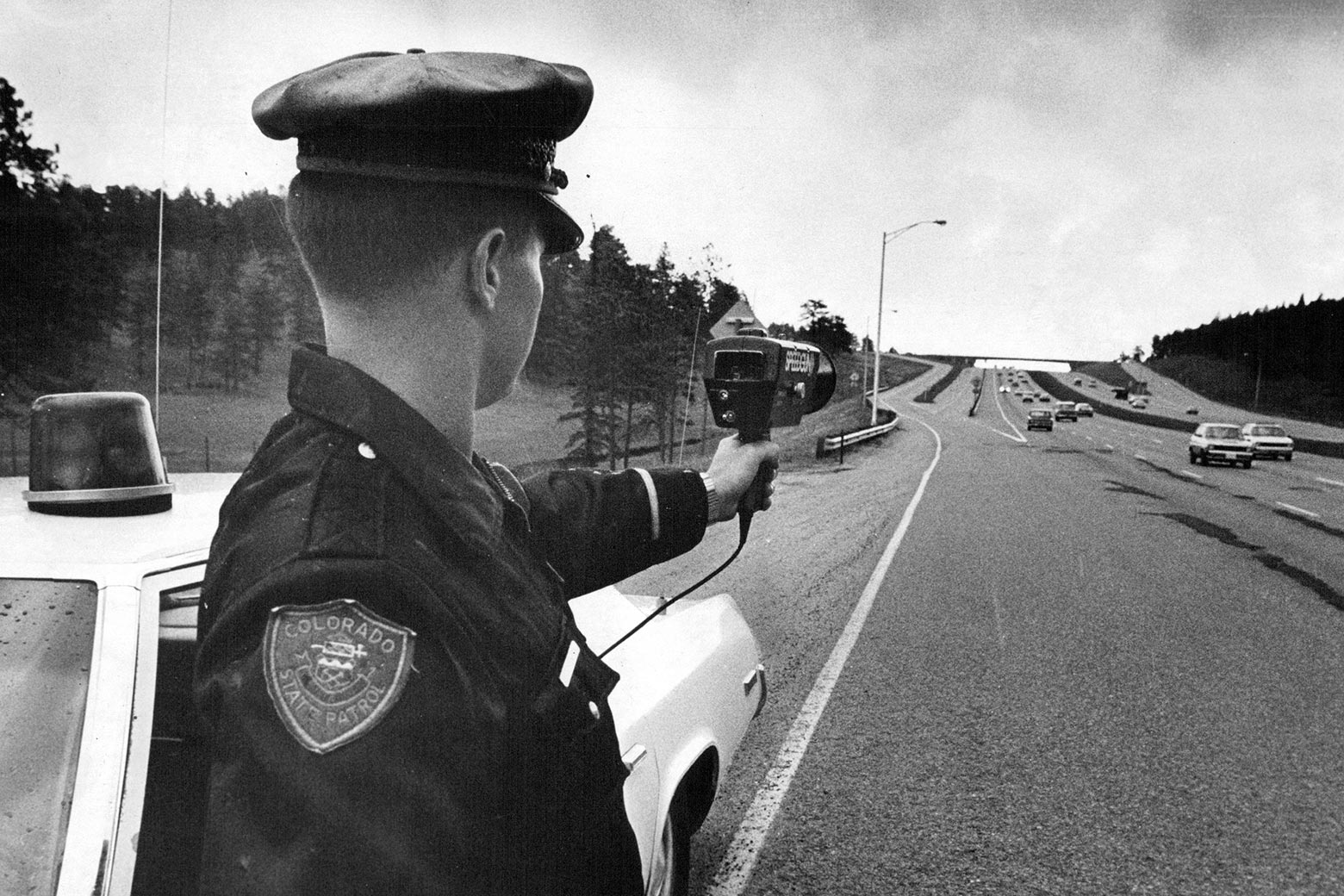

But sometimes that means making good on the threat that’s implicit in all that driving. Roberts rolled into the grass alongside an on-ramp, hidden from oncoming traffic by a sign and a bend in the road. He pulled out a TruSpeed S, a top-of-the-line laser gun that permits him to gauge the speed of passing cars from any angle.* We sat there for about 30 seconds before he clocked a blue Buick doing 90, and then we were off, racing down the highway until we were right behind the car in question.

Speeding is a national health problem and a big reason why this country is increasingly an outlier on traffic safety in the developed world. More than 1 in 4 fatal crashes in the United States involve at least one speeding driver, making speeding a factor in nearly 10,000 deaths each year, in addition to an unknowable number of injuries. Thousands of car crash victims are on foot, and speed is an even more crucial determinant of whether they live or die: The odds of a pedestrian being killed in a collision rise from 10 percent at 23 mph to 75 percent at 50 mph. And we’re now in a moment of particular urgency. Last year, when the pandemic shutdowns lowered total miles traveled by 13 percent, the per-mile death rate rose by 24 percent—the greatest increase in a century, thanks to drivers hitting high velocities on empty roads. “COVID,” Roberts said, “was midnight on the day shift.”

In the first six months of 2021, projected traffic fatalities in the U.S. rose by 18 percent, the largest increase since the U.S. Department of Transportation started counting and double the rate of the previous year’s surge. “We cannot and should not accept these fatalities as simply a part of everyday life in America,” said Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg in a press release.

But we do. Such carnage has not prompted a societal response akin to the movement elicited by drunk driving in the 1980s. Part of the reason is that Americans love driving fast and have confidence in their own abilities. About half admit to going more than 15 over the limit in the past month. Meanwhile, drivers do generally regard their peers’ speeding as a threat to their own safety, and so we have wound up with the worst of both worlds: Thousands of speed-related deaths on the one hand, and on the other, a system of enforcement that is both ineffective and inescapable.

What I was about to do with Trooper Roberts on that fall morning—chase down a driver on the highway, pull over the car, and issue a ticket—is the No. 1 way Americans interact with police and serves as the start of 1 in 3 police shootings. But it doesn’t stop Americans from speeding.

The nation’s most disobeyed law is dysfunctional from top to bottom. The speed limit is alternately too low on interstate highways, giving police discretion to make stops at will, and too high on local roads, creating carnage on neighborhood streets. Enforcement is both inadequate and punitive. The cost is enormous. And the lack of political will to do something about it tracks with George Carlin’s famous observation that everybody going faster than you is a maniac and everybody going slower than you is an idiot. The consensus is: Enforce the speed limit. But not on me, please. Because while it would be nice to save 10,000 lives a year, it sure is fun to drive fast.

It is as strange as cigarettes on airplanes or dating ads in newspapers to think that between 1974 and 1995, the United States maintained a national speed limit of 55 miles per hour in the name of saving lives. It was one of those moments, like the end of the Concorde’s supersonic passenger jet service or the collapse of the Arecibo Telescope, when technology lurched backward.

The 50-state slowdown known as the “double nickel” began in 1973, with President Richard Nixon’s appeal for collective sacrifice. In retaliation for America’s support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, the coalition of Middle Eastern states known as OPEC decided that fall to stop selling oil to the United States. Prices quadrupled. The president wanted Americans to change their ways: He asked gas stations to close on Sundays and businesses to turn off lighted advertisements. Mayors and department stores dimmed Christmas bulbs nationwide. Daylight saving time went year-round in an effort to use less electric light. Thanks to the lowered thermostat, women were permitted to wear pants in the White House.

And Nixon prompted Congress to implement a national speed limit, for the first time since the Second World War. Then it was to conserve rubber; now, the White House hoped, slower and more fuel-efficient driving would save gasoline.

The lower speed limit did not, in the end, have a significant effect on gas consumption. But the law was retained until the Clinton administration because it appeared to have another welcome consequence: saving lives. In the first six months of 1974, highway deaths fell by 23 percent—a decline widely attributed to the national speed limit. At the urging of the U.S. Transportation Secretary Claude Brinegar, Congress made the 55 mph speed limit permanent.

Two decades of culture war ensued, as rural Americans and Republicans turned against the very idea of oil conservation, represented by those double-nickel interstate signs. “To understand the Reagan Democrats, look no further than the fifty-five mile-an-hour speed limit,” writes Dan Albert in the automotive history Are We There Yet? Kansas Sen. Bob Dole spoke up for those who lived in the America of wide-open spaces, defending high-speed driving; Ronald Reagan promised speed limit repeal in his 1980 campaign. A half-dozen states in the Mountain West replaced speeding tickets with $5 “energy wastage” fines. Sammy Hagar sang “I Can’t Drive 55,” and Tara Buckman, in the opening scene of the 1981 blockbuster The Cannonball Run, leapt from a Lamborghini in a spandex jumpsuit to spray-paint a red X across the 55 mph sign—before fleeing from the highway patrol.

Brock Yates, a Car and Driver editor who drove the first Cannonball Baker Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash in 1971, became the law’s foremost public intellectual opponent. His son, Brock Yates Jr., recalled that his father called the law’s supporters “Safety Nazis,” “because they were convinced that speed kills.” Yates Jr. is a driving instructor who, as a 14-year-old, manned the CB radio on that first coast-to-coast sprint. “Most people, without a speed limit, run out of skill and courage at 75 or 80,” he said. “An argument can be made that speed kills. But it’s really the stopping that kills, not the going.”

Calculating the benefit of something so many people want to do against the cost of thousands of deaths can feel a little grotesque. But economists do the cost-benefit analysis nevertheless, and the results for the 55 mph speed limit were soundly in favor of letting people drive faster if you assigned even a fractional wage value to all the wasted, 55-mph highway hours. In short, at higher speeds, many people died, but many more got to work on time.

The Newt Gingrich–led House voted to repeal the federal speed limit in 1995. The issue wasn’t split along party lines. Democrat Nick Rahall II of West Virginia warned that the bill “would turn our nation’s highways into killing fields.” In the Senate, Virginia’s Republican Sen. John Warner protested that “there are some issues in America that override states’ rights,” the national speed limit among them. Ohio GOP Sen. Mike DeWine said simply, “If we raise the speed limit, people will die.” Automotive watchdog Ralph Nader told President Bill Clinton he ought to “express his apologies to the thousands of people—children, women, and men—who will soon lose their lives or be permanently disabled.”

But that did not come to pass. The number of annual auto deaths dropped below 44,000 in 1990 and has not passed that number since; instead, it fell to a 40-year low in 2014, despite enormous growth in the number of cars on the road. Every state has raised the speed limit over the past few decades, with parts of Texas now topping out at 80 mph.

It turns out that calculating the relationship between the speed limit and road safety is surprisingly complicated. In the years since the national speed limit was repealed, both supporters and opponents of speed limits have managed to marshal ample evidence to make their case. On the pro-limit side: In 1984, the National Academy of Sciences reported to Congress that the national speed limit saved 4,000 lives and prevented 3,500 severe injuries and 50,000 minor injuries each year. A study by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety concludes that subsequent increases in speed limits over two decades have cost 33,000 American lives. Annual auto deaths kept falling after repeal, they argue, thanks to unrelated improvements in car safety.

Other researchers have disputed these conclusions. One 1994 survey, for example, looked at crash data since 1987, when many states were permitted to raise speed limits to 65 in rural areas, in a series of carve-outs to the 1974 law, and concluded that the speed limit increase had reduced fatalities by as much as 5 percent, possibly because it encouraged drivers to use the safer, faster interstates and permitted police to redirect their efforts toward more dangerous two-lane roads. Others have surmised that it is less speeding than the difference of speeds that causes accidents, and higher speed limits encourage everyone to drive in a more self-similar fashion, since law abiders accelerate to meet the speed that lawbreakers drive anyway.

Ezra Hauer, a civil engineer and authority on road safety who taught at the University of Toronto, summarized the conflicting data like this: It is hard to prove that crashes are more common when speeds go up. But they are certainly more severe. “It’s pretty well-accepted that speed is positively related to injury,” he said. “You have to decelerate from a certain speed, your internal organs decelerate, collide with your rib cage, your brain collides with your skull. If you increase the average speed by 1 percent, you increase the number of fatalities by 3–4 percent.”

Members of the higher speed limit lobby often point out that raising limits does not necessarily raise speeds. Boosting the speed limit may merely bring the law in line with the observed roadway speed. “When I look at correcting a speed limit, I am not advocating driving faster, and that’s the hard part to get over,” Lt. Gary Megge of the Michigan State Police told a reporter a few years ago.

It is not an exaggeration to say that police power in the United States is built around the unique conditions created by car culture, in which virtually everyone is breaking the law all the time—with occasionally severe consequences. In her book Policing the Open Road, the legal scholar Sarah Seo points out that mass car ownership prompted a wholesale reinterpretation of the Fourth Amendment, which protects us against search and seizure. Or it did, until we all started driving everywhere.

Police often abuse this authority to perform “pretextual stops” hoping to find guns or drugs, knowing that trivial traffic violations give them the power to search citizens at will. Officers have at times undertaken this constitutional sleight of hand with explicit federal endorsement, deputized as foot soldiers in the war on drugs. In one of the most notorious examples, police in Arizona used traffic stops to enforce federal immigration law.

For Black drivers, pretextual traffic stops—per Jay-Z, “doing 55 in a 54”—are a routine occurrence and the foremost symbol of racial profiling in this country. For many police departments, these violations are used to fill government coffers and prompt devastating cycles of fines, debt, suspended driver’s licenses, and jail time. Black drivers are 20 percent more likely to be stopped, according to a study last year, and almost twice as likely to be searched.

Most harmless speeding, the type that most people feel is natural to keep up with the flow of traffic, happens on limited-access highways (roads with merge lanes, exits, and no roadside commerce). That’s where the power of the National Maximum Speed Limit was felt. That’s where the share of drivers going over the speed limit is highest. That’s where the anti–speed limit advocates get their data. But that’s not where most accidents happen. Despite the high speeds, the Interstate Highway System is more than twice as safe per mile as almost any other type of road.

For those reasons, the dichotomy between “speeding” and “not speeding” is not very instructive. The consequences of high speeds vary greatly based on context, in ways that may have little to do with posted speed limits or fines. Go a few miles over the speed limit, and you may still be one of the slower drivers on the road. Go 20 over, and your risk rises exponentially. Speed on a highway and the person you most put at risk is yourself. Speed in a residential neighborhood and you threaten a whole community, from the people on the street to the buildings around them.

Given all this, speeding enforcement could use a tighter focus. Relatively few motorists drive at what the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration calls “extreme speeds” of more than 20 mph over the limit. In the District of Columbia, it was just 6 percent of speeders in 2019. (One of them was going 132 mph in a 50 mph zone.) For a police-based enforcement system to be able to find and stop those drivers would be remarkably good luck. But those are exactly the drivers most likely to hurt themselves or others in a crash.

Enter automated traffic enforcement, or speed cameras, which can reduce encounters between citizens and the police, target extreme speeders, and discourage bad driving. Unlike drunk and distracted driving—the two other great causes of death on the road—speeding can be easily patrolled by machine.

In Europe, speed cameras are ubiquitous and so familiar that “radar” is a readily available Halloween costume for French children. In France and other European countries, it’s almost unheard of to be pulled over by a flashing-lights police cruiser going 85 mph. Instead, roads are lined with radar-enabled cameras that distribute tickets by mail. Speed cameras are a part of the reason Europe’s roads are now much safer than America’s; a 2010 literature review found crashes resulting in death or serious injury fell between 17 and 58 percent where cameras were installed. And because speeding is more rigorously enforced, penalties are smaller than in the United States, where a speeding ticket can set you back hundreds of dollars.

The world’s most developed speed camera network is in New York City. A pilot of 140 cameras installed around city schools in 2014 reduced speeding during school hours by 63 percent and injuries by 14 percent. After an expansion in 2019 to 750 schools, the cameras—which operate between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m.—reduced speeding on average by 72 percent. Crashes near cameras fell too. The cameras only issue tickets to drivers going more than 10 mph over the speed limit.

Brad Lander, New York City’s comptroller-elect, has proposed using this information to target repeat offenders for remedial driving courses or vehicle seizure. Conventional speeding tickets are a pretty lousy data set, since your odds of getting caught are so low. Not so with the information from speed cameras. Unlike on the highway, here it’s meaningful that 59 percent of drivers who get a ticket never get another one, and another 18 percent receive just one more. Small fines and changed behavior: The city’s speed camera program is a model.

Except that it has little power over the worst drivers, who can be easily identified by their repeat violations. Lander’s bill would require drivers to take a course once they accrue more than 15 school zone speeding tickets in a 12-month period. That sounds like a higher number than it is. The driver who lost control in Brooklyn in September, killing a 3-month-old baby, had received 91 camera-issued speeding tickets—including 15 speeding fines in July and August alone.

Some civil rights advocates oppose automated enforcement on the grounds that even race-blind cameras are used to scale up America’s traditions of revenue-driven and racist policing. In D.C., for example, researchers found that drivers in segregated Black neighborhoods received 17 times as many camera tickets per capita as their counterparts in white neighborhoods. Black Washingtonians are indeed more likely to live near high-speed arterials where drivers (including white suburbanites) go very fast, but the disparity suggests the cameras aren’t improving driver safety so much as raising money. America’s one-size-fits-all fine structure is also inherently regressive compared with Finland, where speeding tickets are famously adjusted to match the driver’s income.

Still, the prospect of a well-run speed camera program is enticing for city residents who have watched their neighbors die in both collisions with speeding cars and encounters with police. As the activist Darrell Owens, who successfully pushed Berkeley, California, to remove the police role in traffic enforcement, put it recently, “No one’s ever been shot by a traffic camera.”

“Most people support cameras,” said Kelcie Ralph, who studies speeding at Rutgers and recently completed a national survey on the subject, to be published next year. “There’s a very vocal minority of opposition, and they are very vigilant and show up at meetings. But most people recognize this is a problem and want the government to take action.” The problems with camera programs, she added, could be fixed by designing better systems and directing revenue into nearby infrastructure like sidewalks and curb cuts.

For the moment, though, those squeaky wheels have convinced powerful legislators that speed cameras are some kind of constitutional violation, more invasive than the nation’s existing network of toll cameras and a greater abuse of police power than random highway detentions. What these people really object to is being caught. In the 2021 GOP debate for New York City mayor, eventual Republican nominee Curtis Sliwa said the No. 1 issue facing New Yorkers was not COVID-19, climate change, high rents, or the tax base—but “needless speed cameras.” His opponent agreed. Eight states have banned the use of speed cameras entirely. The prospect of cameras displacing the discretion of state police is, for the moment, implausible.

Speed cameras and speed traps have something in common: They both rely on the wisdom of speed limits, which are not very wise. The conventional wisdom in the field of traffic engineering is that the speed limit should be set according to the 85th percentile rule—at the speed of the 15th-fastest of 100 drivers on the road. City transportation officials do not like this method: The fastest 15 percent of drivers, they argue, are not always the most rational appraisers of what constitutes a safe speed. Nor should drivers’ interests determine the character of a street for its other users. In an essay in the Harvard Law Review, Greg Shill and Sara Bronin write, “The 85th Percentile Rule is perhaps unique in American law in empowering lawbreakers to activate a rewrite of the law to legalize their own unlawful conduct.”

But the 85th percentile rule contains a fundamental truth: Drivers respond to the road they are given. Engineers use this rule to foster a cycle of wider, clearer roads and higher speeds. But the same logic could be employed in the opposite direction, too, in places where drivers and pedestrians interact.

There are three basic changes we could make to America’s roads, cars, and drivers to address speeding at its root. First, we could design roads to keep drivers at safe speeds. In rural areas, that means replacing intersections with roundabouts—a change associated with cutting crash rates by more than 50 percent. In cities, that means narrowing streets and intersections, building out curbs and speed bumps, and changing pavements to materials like paving stones that slow drivers down.

“We’re at the point where the things we have to do may be uncomfortable for people,” said Zabe Bent, the director of design at the National Association of City Transportation Officials. But, she added, many of the city arterials where thousands of pedestrians are killed each year are not in control of local residents and their elected officials, but are instead run by state DOTs. University Avenue in South Florida, Moreland Avenue in Atlanta, Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco: These are just a few roads where local politicians are powerless to change speed limits or roadway designs.

Second, we could do a better job training drivers. American teenagers are by far the most dangerous group of people on the road, with 16- and-17-year-olds more than three times likelier to get into a fatal crash than adults in their 30s or 40s. After 80, drivers again become more dangerous to people around them. “Since we’ve put the onus on the speed limit and the cars, we’ve forgotten the drivers as the most important part,” said Yates, the driving instructor and Cannonball alumnus. “We’ve gotten away from teaching skills—requiring you learn something about the 4,000-pound missile you’re driving.”

Third, we could intervene in the architecture of vehicles themselves. The U.S. auto industry killed the possibility of “speed governors” in cars in the 1920s. Do those arguments hold for self-driving cars as well? Recent technology allows auto regulators to make finer-grain interventions as well, such as intelligent speed assistance, a modest version of which will soon be installed on all vehicles sold in the European Union. When activated, ISA would create resistance under the accelerator when a car surpasses the speed limit.

It’s no surprise that speed limits are being introduced into cars in Europe first; the continent’s anti-speeding movement is gaining ground. At the national level, it’s being driven by green parties’ concerns that how high speeds are bad for gas mileage and emissions. At the local level, city governments are trying to protect pedestrians and bicyclists. Europe has lower speed limits in cities and speed cameras on highways, and those changes have been coupled with rigorous driver education and better street design. In the U.S., meanwhile, we have been reluctant to address any of the root causes of unsafe speeds, preferring instead to play with signage and enforcement.

Like many police, Trooper Kevin Roberts thinks speeding enforcement works, in the sense that it slows down traffic at large. Some experts I spoke to dispute this notion, but I can see why you would think it were so if you drove a police car all day. As a philosophical matter, it does not bother him to be charged with enforcing a law that no one obeys. That’s in part because he knows the speed limit is a coded behavioral guide whose real message, “Don’t go more than 10 mph above this speed,” is widely heeded. It is the legal equivalent of inviting your friends to dinner at 7:30 and knowing the whole party would be there by 8.

But the other thing Roberts said was that there was nothing unusual at all about the speed limit, insofar as it gave the police almost total power to stop and fine drivers at will. “Everything’s illegal,” he said as we watched a line of cars turn in front of us—one, two, three, four. “No front plate. License plate cover. Tinted windows. Following too close. I’m not going to pull over 300 cars. That’s not what people want.” In short, the discretionary power of police is so vast that speeding isn’t so exceptional after all. Except that unlike all those other technicalities, it’s deadly.

After he gave out a ticket, Roberts let me try the speed gun. It resembled binoculars on its outer side, narrowing into one lens for my eye. Using a red target in the lens, I followed a car on the road as the machine emitted a faintly mechanical buzz before concluding with a beep: 56 mph. Beep: 62 mph. Beep: 60 mph. I wondered if I was doing this wrong. And then I remembered: I was in a highly visible police car on the side of the road. Everyone had already slowed down, likely for the first and last time on their morning drive.

Roberts instructed me to look back toward the bend where drivers first saw us. You could actually watch the front of the cars sink as traffic decelerated. Cops call that “dropping the anchor.” It’s a familiar experience for police now that drivers share troopers’ locations on Waze, quashing the element of surprise. Some cops are on Waze too, and they’ll remove themselves. But in some ways, their work is done here. It dawned on me that you could probably get everyone to drive the limit by sticking an empty cop car at various strategic points along the road. No trooper necessary.

A big cold front was moving in, bringing thunderstorms. “It’s going to get messy,” Roberts said. He dropped me off at the barracks, where I got into my own car and headed west on I-84 as the rain began to come down. I didn’t get far before traffic slowed to a crawl. A tow truck passed on the shoulder. After 20 minutes of stopping and starting, I reached the choke point: Three mangled cars on the side of the road, two drivers on the scene, one in an ambulance somewhere ahead.

Correction, March 11, 2022: This piece originally misidentified the TruSpeed S as a radar gun. It is a laser gun.

Correction, Dec. 16, 2021: This piece originally mischaracterized the vest as made of Mylar. It was made of Kevlar.