In some years, more than 40% of all local laws passed by the New York City council have been street name changes. Let me give you a moment to think about that. The city council is congress to the mayor’s president. Its 51 members monitor the country’s largest school system and police force, and decide land use for one of the most densely populated places on Earth. Its budget is larger than most states’, its population bigger than all but 11 states. On top of that, New York’s streets have largely been named or numbered since the 19th century, with some street names, such as Stuyvesant and the Bowery, dating from when Manhattan was little more than a Dutch trading station.

And yet, I’ll say it again: in some years, more than 40% of all local laws passed by the New York City council have been street name changes.

The city council often focuses on honorary street names layered on top of the regular map. So when you walk through the city, you may look up and see that while you are on West 103rd Street, you are also on Humphrey Bogart Place. Or you might be on Broadway and West 65th Street (Leonard Bernstein Place), West 84th (Edgar Allan Poe Street), or East 43rd (David Ben-Gurion Place). Recently, the city council approved the Wu-Tang Clan District in Staten Island, Christopher Wallace Way (after the Notorious BIG.) in Brooklyn and Ramones Way in Queens. The city council co-named 164 streets in 2018 alone.

But in 2007, when the city council rejected a proposal to rename a street for Sonny Carson, a militant black activist, demonstrators took to the streets. Carson had formed the Black Men’s Movement Against Crack, organised marches against police brutality and pushed for community control of schools. But he also advocated violence and espoused unapologetically racist ideas. When a Haitian woman accused a Korean shop owner of assault, Carson organised a boycott of all Korean grocery stores, where protesters urged black people not to give their money to “people who don’t look like us”. Asked if he was antisemitic, Carson responded that he was “antiwhite. Don’t limit my antis to just one group of people.” The mayor at the time, Michael Bloomberg, said: “There’s probably nobody whose name I can come up with who less should have a street named after him in this city than Sonny Carson.”

But supporters of the naming proposal argued that Carson vigorously organised his Brooklyn community long before anyone cared about Brooklyn. Councilman Charles Barron, a former Black Panther, said that Carson, a Korean war veteran, closed more crack houses than the New York police department. Don’t judge his life on his most provocative statements, his supporters asked. Still, Carson was controversial in the African American community as well. When the black councilman Leroy Comrie abstained from the street name vote, Barron’s aide Viola Plummer suggested that his political career was over, even if it took an “assassination”. Comrie was assigned police protection. (Plummer insists she meant a career assassination rather than a literal one.)

When the council finally refused the Carson-naming proposal (while accepting designations for the Law & Order actor Jerry Orbach and the choreographer Alvin Ailey), a few hundred Brooklyn residents flooded into Bedford-Stuyvesant and put up their own Sonny Abubadika Carson Avenue sign on Gates Avenue. Barron pointed out that New York had long honoured flawed men, including Thomas Jefferson, a slave-owning “paedophile”. “We might go street-name-changing crazy around here to get rid of the names of these slave owners,” he called out to the angry crowd.

“Why are leaders of the community spending time worrying about the naming of a street?” Theodore Miraldi of the Bronx wrote to the New York Post. Excellent question, Mr Miraldi. Why do we care this much about any street name at all?

My street address obsession began when I learned for the first time that most households in the world don’t have street addresses. Addresses, the Universal Postal Union argues, are one of the cheapest ways to lift people out of poverty, facilitating access to credit, voting rights and worldwide markets. But this is not just a problem in the developing world. I learned that even parts of the rural US don’t have street addresses.

West Virginia has tackled a decades-long project to name and number its streets. Until 1991, few people outside of West Virginia’s small cities had any street address at all. Then the state caught Verizon inflating its rates and, as part of an unusual settlement, the company agreed to pay $15m (£12.4m) to, quite literally, put West Virginians on the map.

For generations, people had navigated West Virginia in creative ways. Directions are delivered in paragraphs. Look for the white church, the stone church, the brick church, the old elementary school, the old post office, the old sewing factory, the wide turn, the big mural, the tattoo parlour, the drive-in restaurant, the dumpster painted like a cow, the pickup truck in the middle of the field. But, of course, if you live here, you probably don’t need directions; along the dirt lanes that wind through valleys and dry riverbeds, everyone knows everyone else anyway.

Emergency services have rallied for more formal ways of finding people. Close your eyes and try to explain where your house is without using your address. Now try it again, but this time pretend you’re having a stroke. Paramedics rushed to a house in West Virginia described as having chickens out front, only to see that every house had chickens out front. Along those lanes, I was told, people come out on their porches and wave at strangers, so paramedics couldn’t tell who was being friendly and who was flagging them down. Ron Serino, a firefighter in Northfork (population 429) explained how he would tell frantic callers to listen for the blare of the truck’s siren. A game of hide-and-seek would then wind its way through the serpentine hollows. “Getting hotter?” he would ask over the phone. “Getting closer?”

Many streets in rural West Virginia have rural route numbers assigned by the post office, but those numbers aren’t on any map. As one 911 official has said: “We don’t know where that stuff is at.”

Naming one street is hardly a challenge, but how do you go about naming thousands? When I met him, Nick Keller was the soft-spoken addressing coordinator for McDowell County. His office had initially hired a contractor in Vermont to do the addressing, but that effort collapsed and the company left behind hundreds of yellow slips of paper assigning addresses that Keller couldn’t connect to actual houses. (I heard that West Virginia residents, with coal as their primary livelihood, wouldn’t answer a call from a Vermont area code, fearing environmentalists.)

Many people in West Virginia really didn’t want addresses. Sometimes, they just didn’t like their new street name. (A farmer in neighboring Virginia was enraged after his street was named after the banker who denied his grandfather a loan in the Depression.) But often it’s not the particular name, but the naming itself. Everyone knows everyone else, the protesters said again and again. When a 33-year-old man died of an asthma attack after the ambulance got lost, his mother told the newspaper: “All they had to do was stop and ask somebody where we lived.” (Her directions to outsiders? “Coopers ball field, first road on the left, take a sharp right hand turn up the mountain.”)

But as Keller told me: “You’d be surprised at how many people don’t know you at three in the morning.” A paramedic who turns up at the wrong house in the middle of the night might be met with a pistol in the face. One 911 official told me how she tried to talk up the project with McDowell County’s elderly community, a growing percentage of the population now that young people are moving to places with more work. “Some people say: ‘I don’t want an address,’” she told me. “I say: ‘What if you need an ambulance?’” Their answer? “We don’t need ambulances. We take care of ourselves.”

“Addressing isn’t for sissies,” an addressing coordinator once told a national convention. Employees sent out to name the streets in West Virginia have been greeted by men with four-wheelers and shotguns. One city employee came across a man with a machete stuck in his back pocket. “How bad did he need that address?”

Some people I spoke to saw the area’s lack of addresses as emblematic of a backward rural community, but I didn’t see it that way. McDowell County struggles as one of the poorest counties in the country, but it’s a tight-knit community, where residents know both their neighbours and the rich history of their land. They see things outsiders don’t see. I, on the other hand, now use GPS to navigate the town I grew up in. I wondered whether we might see our spaces differently if we didn’t have addresses. And far from being outlandish, the residents’ fears turn out to be justifiable, even reasonable. Addresses aren’t just for emergency services. They also exist so people can find you, police you, tax you and try to sell you things you don’t need through the mail.

Street addresses tell a complex story of how the grand Enlightenment project to name and number our streets coincided with a revolution in how we lead our lives and how we shape our societies. And rather than just a mere administrative detail, street names are about identity, wealth and, as in the Sonny Carson street example, race. But most of all they are about power – the power to name, the power to shape history, the power to decide who counts, who doesn’t, and why.

Today, rural West Virginians at last have organised street addresses. But what about the billions around the world who do not?

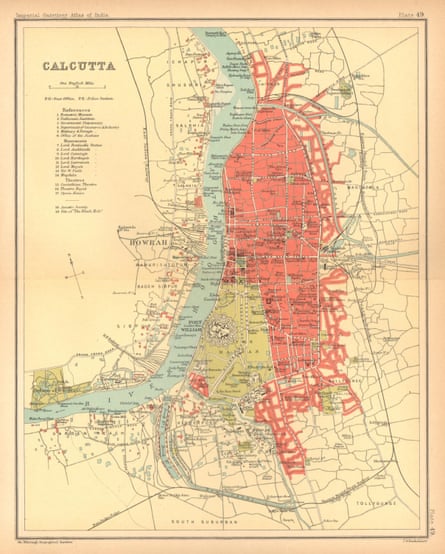

Subhashis Nath is a social worker and senior manager for Addressing the Unaddressed, an NGO with the sole mission to give street addresses to every slum in India, starting in Kolkata. On a sunny February day, I went with him to Chetla, an old slum squeezed in between a canal and a railroad. In some ways, I found Chetla a bit of a relief from the centre of the city. The slum is densely packed, but perhaps because its residents have often come from villages, it felt oddly rural.

The slums seemed to have more serious needs than addresses – sanitation, clean water, healthcare, even roofs to protect them from the monsoon. But the lack of addresses was depriving those living in the slums a chance to get out of them.

Without an address, it’s nearly impossible to get a bank account. And without a bank account, you can’t save money, borrow money or receive a state pension. Scandals had exposed moneylenders and scam banks operating throughout Kolkata’s slums, with some residents reportedly killing themselves after losing their life savings to a crook. With their new addresses, more residents of Chetla can now have ATM cards.

“Slum” is an umbrella term for a wide range of settlements. Most slums, arising along canals, roadsides, or vacant land are illegal – the inhabitants are squatters, living without permission on someone else’s land. Others are “bustees”, or legal slums, often with higher-quality housing, where the tenants lease their land.

Still, the slums often have much in common: poor ventilation, limited clean water supplies and a scarcity of toilets and sewage systems. One government definition describes a slum’s structures as “huddled together”, a term I thought more literary than technical until I saw shacks literally leaning on each other for support. The estimated 3 million Kolkatans who live in the city’s 5,000 slums are often the luckier ones; at least they have some shelter. The poorest, the sidewalk-dwellers, sleep on the streets, babies pressed carefully between couples on the sidewalks. Even though rickshaws are technically banned, near-naked men in bare feet still jog their charges along the filthy streets.

Some slums are nicer than others. The ones closer to the city, like Chetla, are often hundreds of years old, with pukka houses made of concrete, tin roofs and real floors. In Panchanantala, a name I find excuses to keep saying, about 20 teenage girls sat in bright saris in the middle of what seemed to be the main street, singing joyfully to a Hindu shrine, while people milled around, buying fruit and vegetables from local vendors.

Then Subhashis and his colleague Romio took me to Bhagar, where skyscrapers of rubbish greet you at the entrance. Women and children scrambled over the heaps of garbage, rooting out anything valuable, while trucks lined up to add to the towers of trash. The hogs that rooted along the lanes were a source of extra income for their families. (Makeshift butchers hung slabs of bloody pork from the ceilings of their shacks, swarms of flies buzzing.) I watched a girl bathe carefully in an inky black lake that, I was told, sometimes spontaneously catches fire because of the chemicals from the dump. And yet, even those in Bhagar were better off than many, Subhashis told me. At least the dump gave them an income.

In Bhagar, Subhashis pulled out his computer and wiped his face, staining his T-shirt black with soot from the smoke. The team had already given Bhagar addresses, but he and Romio had come to update the addresses of new, makeshift structures that had been built in the meantime. Slums are always shifting and changing; houses are razed and rise again; families come from the village and return. Some new families now lived on the verandas of the homes, sleeping next to chained-up goats. Subhashis and Romio assigned each an address, constantly comparing their records to the new structures in front of them. So much had changed since the last time they had been there. I had a feeling they would be back soon.

In the 80s, the World Bank was zeroing in on one of the driving forces behind poor economic growth in the developing world: insecure land ownership. In other words, there was no centralised database of who owned any given property, which made it difficult to buy or sell land, or use it to get credit. And it’s hard to tax land when you don’t know who owns it. Ideally, countries would have cadastres, public databases that register the location, ownership and value of land. A good cadastral system makes the buying and selling of land, as well as the collection of taxes, easy. When you buy a piece of land, you (and the government’s tax offices) can be sure that you – and you alone – own it.

But the cadastral projects run by the World Bank frequently failed. Poor countries didn’t have the resources to keep up the databases. A cadastre could be corrupt, too, if officials put in the wrong information, stripping rightful owners of their titles.

And instead of creating a simple registry, highly paid consultants designed high-tech, computerised systems that became overly complex to manage. Millions of dollars were sunk into never-ending projects that didn’t go anywhere. Organisations like the World Bank and the Universal Postal Union struck on an easier way. It wasn’t just that developing countries lacked cadastres – they also lacked street addresses. Addresses allowed cities, as some experts wrote, to “begin at the beginning”. With street addresses, you could find residents, collect information, maintain infrastructure and create maps of the city that everyone could use.

Specialists began to train administrators intensively in how to address their cities. Chad, Burkina Faso, Guinea and Mali all became early adopters. World Bank staff wrote books, designed an online course for street addressing, and even sponsored a competition to come up with a board game to advertise the benefits of addressing.

The benefits were almost immediately obvious. Street addresses boosted democracy, allowing for easier voter registration and mapping of voting districts. They strengthened security, as unaddressed territories make it easy for crime to flourish. (On a less positive note, they also make it easy to find political dissidents.)

Water and electric companies had been forced to create their own systems for collecting bills and maintaining infrastructure – a street addressing system made that task far easier. Governments could more easily identify taxpayers and collect what they were owed. Researchers found a positive correlation between street addresses and income, and places with street addresses had lower levels of income inequality than places that did not. All this, for pennies a person.

These are all the reasons why Addressing the Unaddressed, which is based in Ireland, sees its work as so important. Months before I arrived in Kolkata, I met Alex Pigot, the charismatic co-founder of Addressing the Unaddressed, 5,000 miles away in Dublin. Pigot is a businessman, with distinguished white hair, a salt-and-paprika beard and an elegantly rumpled linen jacket. He started out as a Christmas postman in Ireland in the 70s, and later began a mailing business in the 80s. Mailing services only work with accurate street addresses, so he quickly became an expert.

At a meeting, he happened to run into an Irishwoman named Maureen Forrest who had started a charity called called The Hope Foundation in Kolkata. Forrest told him she was looking for help to do a census of the slums the charity served. Pigot offered the only real expertise he had: addresses.

It wasn’t as easy as he thought it would be. In Kolkata, the houses in many slums were no bigger than the restaurant booth we were sitting in, so he had to tweak the technology. He had to scrap the original plastic placards for the addresses because residents worried they would fall off their doors and cows would eat them. Originally, the team had printed maps of the slums, complete with each home’s new “GO Code”, on large plastic sheets so people could find their way around. But they soon disappeared, as residents used the sheets to plug holes in their roofs during the monsoons. But slowly Pigot and the Addressing the Unaddressed team began to develop systems that worked.

One day in Kolkata, I went with Subhashis and his colleagues to Sicklane, a slum near Kolkata’s port, where trucks flying by stir up dust all day, every day. In an alley so narrow two people could not stand side by side, one of Subhashis’s crew held a computer in one arm, with a map of the slum on the screen. He pinpointed on the map where the house was, clicked on it, and a GO Code appeared. He read the number out to another employee, who wrote it neatly on the door of the home, which had once been, by all appearances, the entrance to a ladies’ room.

They would return and install the official numbers – thick blue placards, the length of my forearm – above the doors. (Soon after I left Kolkata, Google partnered with Addressing the Unaddressed, and together, they are now using the company’s Plus Codes addressing system.) It was hard to see what an address could possibly do for most of these people. If nothing else, I thought, it would make the feel included.

Inclusion is one of the secret weapons of street addresses. Employees at the World Bank soon found that addresses were helping to empower the people who lived there by helping them to feel a part of society. This is particularly true in slum areas. “A citizen is not an anonymous entity lost in the urban jungle and known only by his relatives and co-workers; he has an established identity,” a group of experts wrote in a book on street addressing. Citizens should have a way to “reach and be reached by associations and government agencies,” and to be reached by fellow citizens, even ones they didn’t know before. In other words, without an address, you are limited to communicating only with people who know you. And it’s often people who don’t know you who can most help you.

This sense of civic identity is particularly important in slum areas, where people are, by definition, living on the edge of society. It’s also why there’s reason to be skeptical of organisations like Addressing the Unaddressed. Rather than incorporating the slums into the existing address system in Kolkata, Addressing the Unaddressed was assigning a new kind of address, reserved for the slums alone. They weren’t incorporating the slums into the rest of the city; you might argue they were doing the opposite.

In a way, I agree with that critique. It would be so much better if the address system could unite these two Kolkatas living side by side. I liked the thought that the people in the slums would belong to the rest of the city, not just to each other. But, as I write, the city government seems unwilling or unable to include them. So, for now, they have Subhashis.

As Subhashis and I had walked on the dusty road out of Bhagar, the slum that coexisted with the towering, smoking dump, Subhashis told me that Bhagar’s main problem was that it didn’t have proper communication with the rest of the city. I didn’t understand what he meant until l realised that he was probably using the word “communication” where I would have said “transportation”.

Reaching the slum had required taking four different forms of transport over the Hooghly River, including a kind of open-air vehicle like the ones you ride on in airports. An estimated 150,000 pedestrians (and 100,000 cars) cross the cantilever bridge each day, and the steel joints are wearing out, in part because of the collective tobacco-like gutka chewed and spat on the bridge. We were lucky to be riding in a taxi most of the way, but we still had to get out and walk when it refused to take us any closer to the slum.

Now I thought maybe “communication” was the right word, after all. Bhagar was cut off physically from the rest of Kolkata, but the rest of the world was also cut off from it. Nobody besides the dump truck drivers ever had to see how its residents lived. Addresses, it seemed, might offer one way to tell them.

This is an edited extract from The Address Book by Deirdre Mask, published by Profile on 2 April. You can pre-order a copy from the Guardian Bookshop here.